Dystopian Realities: Cities and Slums.

From the desk of Vitasta Raina

Time: Irrelevant

However, social segregation on account of housing is not a new phenomenon and has been the subject of much study. In the city of Mumbai, under the Slum Rehabilitation Authority, or under Sec 33 (10) of the Development Control Regulations of Mumbai that outlines the regulations for redevelopment of slums in Mumbai, a peculiar situation occurs, where separations or partitions between "rehab structures" (buildings meant to accommodate existing slum dwellers on plots under redevelopment) and "sale structures" (buildings with flats meant to be sold in the free market) are planned in the same location in close proximity to each other. In these cases, while on ground, the cross cultural exchange between young people from differing backgrounds and socioeconomic classes may lead to a rich and vibrant atmosphere for sparking educative, artistic and communal innovations, the divisions created by physical infrastructures and the provision of amenities, along with the erection of walls for privacy and safety, produce instead an atmosphere of deprivation. In their materiality and aesthetic design and in the arrangement of basic civic amenities, and then in the establishment of cooperative housing societies, the "colonies" created in these often high-rise structures, reminds me of J.G. Ballard's High-rise, which explores the psychological impacts of living in modern technosocial landscapes.

Privacy itself is a vital element of human well-being. The loss of privacy often leads to a loss of freedom, and a life of debilitating humiliation and debasement. While digital surveillance leads to the stifling of ideas and innovations, the effects of loss of physical privacy accompanies a breakdown of society and eliminates the agency of the individual, leading to a dehumanised life. While physical surveillance technology is required to a certain extent for keeping tabs on crime on the streets, the cost of loss of privacy has a profound impact on power transactions within cities and slum settlements. While on one hand, this loss is directly reflected in the formation of close knit communities within slum pockets, on the other hand, within the community, the weakest agents, children and women, often lack control over themselves and their individual (physical) boundaries. These themes of loss of privacy, freedom and free-will in a techo-modern age are explored by TV shows like Black Mirror, and Philip K Dick's The Minority Report.

Time: Irrelevant

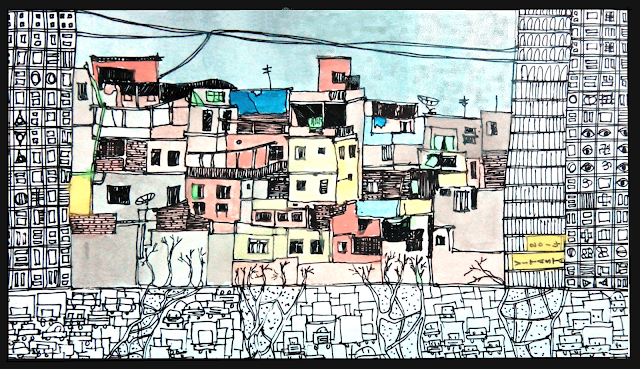

There have been many romanticised accounts of Indian Slums in film, in literature and even in the field of urban research and planning. There is something quite striking about unauthorised structures, the walls that rise out of desperation from the damp filthy ground, that traverse the planes and angles of human need, instinctive, organic and fundamentally raw and naïve, akin to an Art Brut sculpture, or paintings with myriad contrasting colours, textures and materials. In their granularity, irregular geometry and almost chaotic built vocabulary, these walls of often 3 or 4 storey high living structures offer Indian Cities, particularly large metros like New Delhi and Mumbai, a sort of aesthetic departure that borders on a strange enigmatic revulsion, a centrifugal force that pins you inwards towards its horror, and then shreds your senses apart as you spin closer to its frame.

These structures offer Indian cities a peculiar insight into possible dystopian futures, particularly in the wake of “Smart Cities” and the pervasive technologies that it encompasses.

For readers of Science-Fiction, describing a Dystopian setting becomes easier, but in its most basic sense, a dystopia is simply an ‘anti-utopia’, where utopia would imply an ideal society, and dystopia the exact opposite, a complete civic collapse and a degenerative, decaying society, and more often than not, a dictatorial iron-boot bureaucratic and governance control. If we take a step back and look at the world we are creating in our cities, where we don’t have ‘gated societies’ any more than have mini walled anti-cities, or walled cities within the municipal boundaries of a city, surrounded by informal colonies and islands of institutional and recreational uses. These townships, large and small, are designed to keep out the working masses, human and animal trash alike, and are not much different than medieval walled cities (dark ages). These scenarios, of a jailed-in gentry, albeit by their own free will, draws parallels with hit TV shows like The Walking Dead, where a growing disempowered population and climate-change led food shortages no longer seems to be an unlikely scenario.

However, social segregation on account of housing is not a new phenomenon and has been the subject of much study. In the city of Mumbai, under the Slum Rehabilitation Authority, or under Sec 33 (10) of the Development Control Regulations of Mumbai that outlines the regulations for redevelopment of slums in Mumbai, a peculiar situation occurs, where separations or partitions between "rehab structures" (buildings meant to accommodate existing slum dwellers on plots under redevelopment) and "sale structures" (buildings with flats meant to be sold in the free market) are planned in the same location in close proximity to each other. In these cases, while on ground, the cross cultural exchange between young people from differing backgrounds and socioeconomic classes may lead to a rich and vibrant atmosphere for sparking educative, artistic and communal innovations, the divisions created by physical infrastructures and the provision of amenities, along with the erection of walls for privacy and safety, produce instead an atmosphere of deprivation. In their materiality and aesthetic design and in the arrangement of basic civic amenities, and then in the establishment of cooperative housing societies, the "colonies" created in these often high-rise structures, reminds me of J.G. Ballard's High-rise, which explores the psychological impacts of living in modern technosocial landscapes.

|

| The Walls of War. (c) Vitasta Raina, 2014 |

One of the more insidious effects of advancement in technology is the change it brings in the notions of privacy. While on one hand, the upper classes are struggling to come to grips with big data scandals and the erosion of "digital" privacy, a term which has recently found itself in the mainstream with the Facebook data leaks, on the other hand, over-congestion under tin-roofed, single room residential spaces in unauthorised colonies and slums has already led to a steady erosion of physical notions of privacy. Both ideas of privacy often find their way into dystopian literature settings (1984, The Handmaid's Tale), and with the coming of CCTV and smart surveillance tech in walled cities and their counterpart slum settlements, the idea of a technocratic machine (or corporation) in-charge of delivery of municipal utilities and services becomes more concrete. For instance, city corporations (SPVs) in-charge of setting out the action plans for smart cities are paving the way for contemporary "city-states", and the fragmented and dissimilar attributes of Indian cities on ground become simultaneously "more manageable" in the formal systems of built and social environments, and equally "more chaotic" in the informal systems of cities. This distortion comes forth in the form of exacting contrasts, where "middle class values" of "shame", "identity" and "community" are constantly challenged.

Privacy itself is a vital element of human well-being. The loss of privacy often leads to a loss of freedom, and a life of debilitating humiliation and debasement. While digital surveillance leads to the stifling of ideas and innovations, the effects of loss of physical privacy accompanies a breakdown of society and eliminates the agency of the individual, leading to a dehumanised life. While physical surveillance technology is required to a certain extent for keeping tabs on crime on the streets, the cost of loss of privacy has a profound impact on power transactions within cities and slum settlements. While on one hand, this loss is directly reflected in the formation of close knit communities within slum pockets, on the other hand, within the community, the weakest agents, children and women, often lack control over themselves and their individual (physical) boundaries. These themes of loss of privacy, freedom and free-will in a techo-modern age are explored by TV shows like Black Mirror, and Philip K Dick's The Minority Report.

Most dystopian work in art, literature or films is built on a worst case scenario of existing conditions, a sort of mirror world calling to attention the divergences of modern urban ethno-cultures, which creates the possibility of living in an extreme state, of overpopulation, war, climate-change led food shortages, or epidemic outbreaks for instance, in the near future. The one thing that ties in together however, with dystopian settings are, more often than not, autocratic governance mechanisms that repress human freedom, especially the freedom of expression.

For now, the informal walls of slum housing offer the more imaginative amongst us, an informally cut and painted canvas on which to tether our stories, and our apirational balloons, while the divide between the regulated city and the unchecked slum creates multiple dystopian realities through which we all transit.

*

More on this at another time.

You can email me at vitastaraina@gmail.com or leave a comment to start a discussion.

*

Peace. Bombay Love.

For now, the informal walls of slum housing offer the more imaginative amongst us, an informally cut and painted canvas on which to tether our stories, and our apirational balloons, while the divide between the regulated city and the unchecked slum creates multiple dystopian realities through which we all transit.

*

More on this at another time.

You can email me at vitastaraina@gmail.com or leave a comment to start a discussion.

*

Peace. Bombay Love.

Comments

Post a Comment