The Spatiality of Relationships in Mumbai

From the desk of Vitasta Raina

Dated: Christmas Eve

Time: Irrelevant

In Edward Soja’s Seeking Spatial Justice, he describes individuals as not only social and temporal beings, but also assemblages of spatial realities. That it’s not only our histories and our social relationships, but also our geographies that make and inform our sense of ourselves. While there has been much literature such as Proshansky’s The City and Self-Identity that delves into the concept of place-identity being an essential part of an individual’s self-identity, the spatial relationships that Soja describes are reflections of an individual’s geography in relation to others, and not necessarily an inherent part of the individual’s identity in itself.

This concept has become fascinating to me as I commute to work from a northern suburb of Mumbai to its CBD in the south on a daily basis. I have seen the birth and sometimes death of many franchise coffee shops and branded restaurants as I make my daily journey up and down the different micromarkets of Mumbai. And it makes me think, how this aspect of spatiality of an individual’s social relationships has been capitalized by the real estate industry.

You see, most relationship in Mumbai, where friends live in different neighbourhoods, divided by thick traffic jams more than kilometres, tends to become no different than long-distance relationships. In the digital age, keeping in touch with each other is easy, but ‘hanging out’ with each other face-to-face becomes a rare event when individuals do not share the same pin-code. We can look into the concepts of balanced urban development, or self-sustainable neighbourhoods, with adequate social infrastructure such as hospitals, schools and playgrounds; but how do you make a neighbourhood attractive enough to bring friends down to meet you in Kandivali say, instead of you having to travel to their more ‘happening’ locality in Khar, because that is ‘where it’s at!”

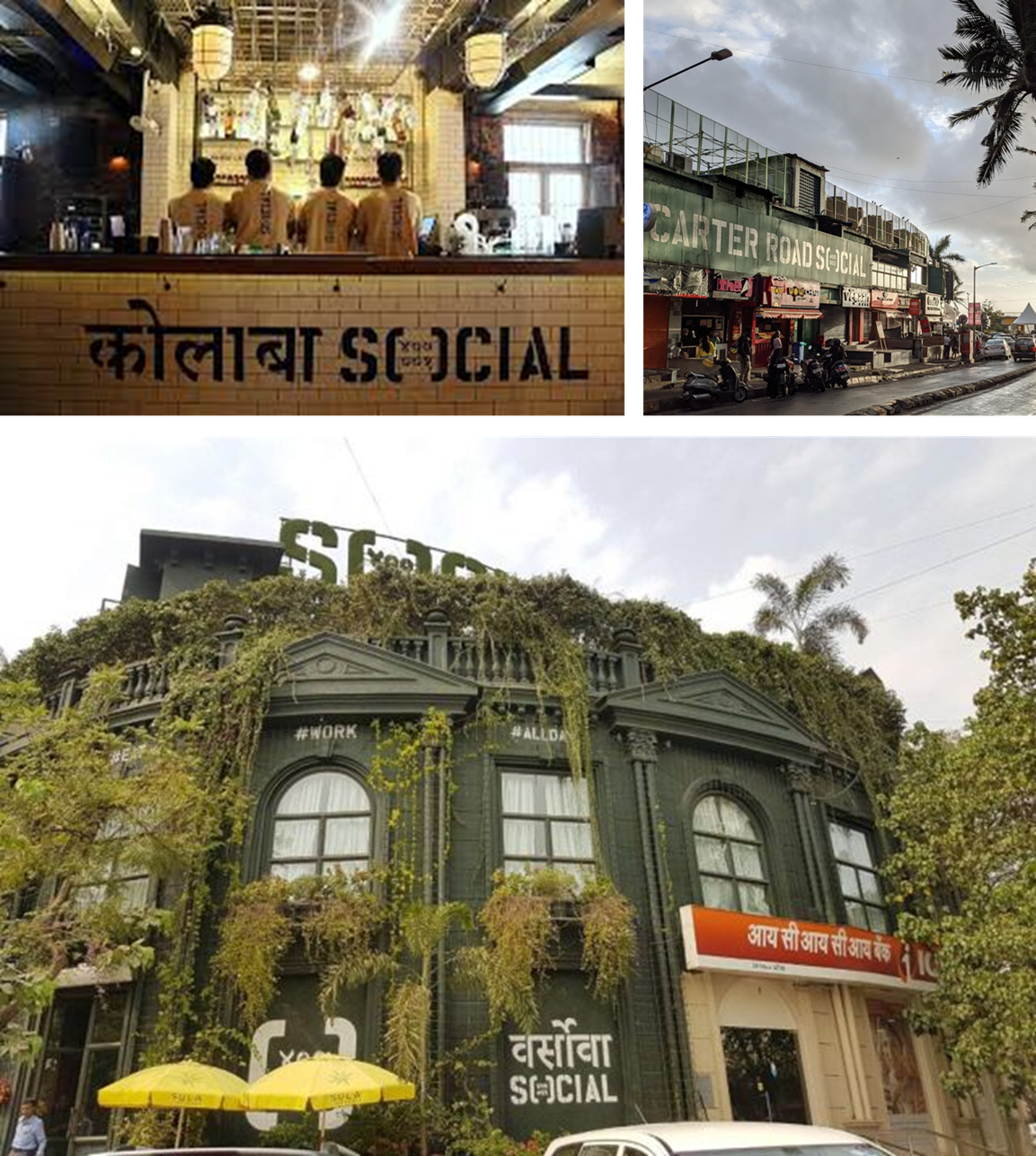

So, we have an interesting phenomenon of resto-bars like Social opening up across neighbourhoods in Mumbai, providing a similar vibe in terms of décor, food choices and music. The only difference is that you do not need to sit through a two hour long traffic jam to experience it. While some might consider it a positive attribute of ‘balanced development’, it is a symptom of the hidden spatial divide brought on by the real estate industry in the city.

|

| The Many Locations of Mumbai's Socials |

Several scholars and organizations such as the Human Rights Watch have written about the ‘Hidden Apartheid’ in India with respect to the caste and religion based socio-spatial segregation in urban and rural areas in the country. We can see caste/tribe/religion based discrimination in rental markets in even more urbane cities such as Mumbai and Bengaluru. Certain localities are formed along community/religion based lines and these divisions are quite rigid. While the concept of ‘territorial stigmatization’ was introduced by Loic Wacquant to describe spaces within a city occupied by marginalized communities, in Mumbai, because of segregation practices by real estate developers, there is a phenomenon of ‘territorial honorification’.

Large real estate players in Mumbai are very specific when it comes to creating “communities” as they don’t sell flats to Muslims. Some developers go so far as to build ‘Jain Temples’ within their gated residential developments to attract a certain type of customer. However, the reverse is also true, where builders in some localities have created Muslim only complexes. However, real estate follows the money, and these spatial divides are a reflection of existing societal divides. Spatial segregation thus is only a mirror of a deeply divided society.

In his book The Production of Space, Henri Lefebvre conceptualized the spatial triad made up of ‘perceived space or spatial practices’, ‘conceived space or the representations of space’ and ‘lived space or representational space’. He argued that capitalist societies produce abstract space, which is characterized by the dominance of mental space over the physical and social ones. In other words, conceived space becomes the dominant space in society and influences perceived and lived spaces. This framework allows us to understand how the real estate industry exerts control over city by distorting the value of land based on ‘branding’. Localities such as Altamount Road are branded as ‘Billionaire’s Row’, and Worli is projected as the ‘Manhattan of Mumbai’. This commodification changes how the neighbourhoods are conceived, which in turn informs their land uses (spatial practices). Thus, luxury malls, gated apartments complexes and second home villa developments come to define “high-value micromarkets”, and entire cities transform into speculative assets.

Which brings us back to the curious case of Mumbai’s Socials. I’d like to argue that the real estate industry is trying to capitalize on an individual’s spatial relationships by creating marketable environments in what may be considered ‘fast-growing’ real estate micromarkets. But this commodification of spaces strips them of their ‘aura’, a term I’m borrowing from Walter Benjamin. This is why dive bars like Janata still act as melting pots bringing individuals from across the city’s geography together over Old Monk and a shared plate of prawns.

But what does this mean in the end? Do we value socially connected friendships more than spatially connected ones especially in an increasingly interconnected digital world? Has Netflix and binge-watch culture changed how much time we spend connecting with our social networks? Has the mismanagement of traffic fundamentally changed the way we interact with shared public spaces like SOBO’s Marine Drive or Malad’s Aksa beach? It’s difficult to tell in a city perpetually being reshaped by the forces of real estate.

*

*

Comments

Post a Comment