Souvenir Spaces: Design Thinking Behind Public Spaces

From the desk of Vitasta Raina

Time: Irrelevant

Notes: Originally written while I was engaged with the Smart Cities Mission programme at the NIUA, New Delhi. Updated and molded after migrating to Mumbai-Pune.

During my tenure with the NIUA, I was exposed to the workings and proposals of the various Smart Cities under the mission, and I was quite fascinated with the Area Based Development (ABD) portion of these proposals and their ideas of creating public spaces that would cater to the needs of all sections of society within the city, or at least to all sections in proximity to the location of the ABD. These spaces were to be pinnacles of urban design, cleanly cut and shaped to world-class standards, but I couldn't help but wonder if such places could truly represent the spirit of Indian cities and their vibrant, messy streets. And that was my key takeaway from that exercise I believe, the lesson that I could draw out about the Work of Architecture in an Age of Industry, Information Technology and Smart Cities, an essay I was writing at that time,- to mold subversion and design consciousness within urban planning and development programmes.

Time: Irrelevant

Notes: Originally written while I was engaged with the Smart Cities Mission programme at the NIUA, New Delhi. Updated and molded after migrating to Mumbai-Pune.

During my tenure with the NIUA, I was exposed to the workings and proposals of the various Smart Cities under the mission, and I was quite fascinated with the Area Based Development (ABD) portion of these proposals and their ideas of creating public spaces that would cater to the needs of all sections of society within the city, or at least to all sections in proximity to the location of the ABD. These spaces were to be pinnacles of urban design, cleanly cut and shaped to world-class standards, but I couldn't help but wonder if such places could truly represent the spirit of Indian cities and their vibrant, messy streets. And that was my key takeaway from that exercise I believe, the lesson that I could draw out about the Work of Architecture in an Age of Industry, Information Technology and Smart Cities, an essay I was writing at that time,- to mold subversion and design consciousness within urban planning and development programmes.

One of the ideas that I explored for the merger of unplanned or spontaneous structures within the paradigm of Smart City Planned development was the creation of 'Souvenir Spaces', which allow architects and city planning experts to build in the messy vitality of Indian cities and streets into future planned areas. While we are often nostalgic about the kind of spaces- built-weathering surfaces and memoryscapes, which transport us to a location in space time where we feel 'at-home in a public-place', it is easy to picture why 'Smart' Cities may not be equipped to deliver these.

Souvenir Spaces is a term which I am using to describe a public place that gives us a strong personal memory, shaping an experience, or a series of experiences that we carry with us through time. At the heart of this discussion is the design of Indian SEZeque cities like GIFT City in Gujarat, and Lavasa, which is fairly close to Pune, my hometown.

Souvenir Spaces are psychological spaces linked to our memories that help us develop a sense of belonging within the spatial dimensions of a given place, as we move along our frame of reference on our timelines. Since each individual moves on his own time axis within a given space, each individual experiences space from his own unique frame of reference. Public spaces are places where many individual develop their memoryscapes. In smart cities in particular, these places gain prominence since the role of architects is currently limited to private properties and very seldom are design architects involved with the development and planning of large public properties such as sidewalks, road junctions and metro stations. Indian Cities in particular look towards public arts to infuse a sense of place in public arenas, but the clear function of architecture as a tool to bind and bring together the image of a city, collectively, is yet to be carved out.

Souvenir Spaces within the narrative of my essay, includes points inside the city where I (as an individual inhabiting the city) developed, lived and planned out my poetic expressions, artwork, and personal relationships. These spaces allow me to weave together and draw order in an other chaotic and seemingly diverse set of spaces, ideas and themes, with multiple actors and built spaces across cities and states with varying levels of infrastructure, and planning standards. Because it belongs with a framework developed entirely from an individual perspective, these spaces are also private spaces. However, while talking about cities and their collective memoryspaces, Souvenir Spaces need to connect with multiple identities and diverse narratives.

The public spaces presented in the Lavasa model of planned cities, jump the necessary evolutionary phases from being nothing to being a break-out space, before becoming more commercial, retail oriented and mainstream. Such spaces lack the experience of weathered memory, of being part of a struggle against an established norm, and therefore lack the meaning and the depth of historical association. Great public places need to go through the cycle of revival, high-culture, main-streaming and stagnation, and therefore when we manufacture a space by breaking the cycle, it becomes a linear experience, and unlike a cycle, it simply slows down and eventually dies. History, whether we create it ourselves, or whether it is handed down to us culturally ensures that a cycle based on nostalgic understanding goes though a period of redundancy and revival. It is indeed true that we tend to 'revive' places we form attachments with. For smart cities to be able to form attachments, they need to create spaces that allow the making of lived histories. In an other example of landuse for public space, Corbusier's Chandigarh was designed with large loosely defined open spaces, rather than rigid, manufactured public plazas, which allowed people the freedom to synthesize the kind of spaces they wanted for themselves. By giving people the power to create a layer of themselves (lived histories) over space, Chandigarh has managed to revive it's one stagnating spaces.

One of the aspects that we must understand is that 'great public spaces' are spaces were 'great' memories are formed. We may not like to admit it as urban planners and designers, but we cannot control how spatial quality psychological affects people, on the scale of a street to city. While architects may be successful in affecting people within the influence zone of a perceivable built environment, it is not possible for us to exercise that degree of control over ever increasing cities, both in sheer size (density/sqkm) and complexity. With Corbusier's Chandigarh model as a middling ground for planned cities we love to hate, but love nevertheless, we need to admit that people make great public spaces, whether a built environment is present or not. However, for people to be able to make spaces 'great' we as planners must allow 'diversity' and 'spatial complexity' to come face to face with each other. It is not an accident that when nature meets the exuberance of youth and when the very rich mingle with the very poor, the sparks of social innovation set fire to the machinery of critical thought, the very essence of humanity's purpose on the planet.

There is another aspect that we must understand when we speak about Souvenir Spaces, that is when we link the spatial quality of spaces with the ability to invoke us in psychological terms, we inherently link it to an experienced or felt temporal space. In simpler terms, a space will only mean something to us, if it reminds us of a pleasant lived experience, that is, it will make us nostalgic, or melancholic, and invoke in us a sense of 'longing' or perhaps even 'belonging'. However, it becomes essential to understand the Memory Retrieval Curve here, because different age-groups tend to use or experience similar spaces in different ways as they are forming (or remembering) memories. Over the course of our life, we go back to the memories we formed between the ages of 10 and 30, and it is perhaps for this age group that making public spaces 'great' or 'smart' is not particularly essential, but rather making them free (flexible from a regulatory perspective), informally governed, and completely 'safe'. This is one of the primary reasons for looking into what is refered to as 'Child friendly cities', but it is more than merely 'safety', as it is with creating memorable spaces with safety as an inbuilt device.

Anyway, in the end, one of the key reasons why 'Smart Cities' are failing to appeal to our sensibilities though 'planned cities' are not a new phenomenon in the Indian planning scenario is because of the way they are defined. Current definitions look at smart cities as 'using technology for achievement of goals'. This in itself is a reflection of consumerism in the very idea of a Smart City. It would perhaps be pragmatic if we shift our definition from 'using technology for fulfillment of needs'. Of course such thinking would need a paradigm shift in moving from antibiotic to more symbiotic associations with nature, and with ourselves.

One of the things that I want to make clear here about Souvenir Spaces within the paradigm of architectural studies is the 'unboxing' of these spaces. Think of it like a series of cubes that are moving forward in time together, as well as moving laterally, that is, shifting places with each other simultaneously as well as chaotically (randomly). It is therefore is hard to illustrate such spaces and to plan them, and any depiction of such images would not sufficiently capture the dynamic nature of these places. However, it is possible through Films to tell these stories. This discussion would take us firmly into Walter Benjamin Territory, and that is a discussion for a different time.

This makes designing Souvenir Spaces in the public realm exceptionally difficult because now, the individual experiencing the present is no longer a single point perspective, but rather a collective. These discussions are particularly important, especially in the realm of housing studies. Housing, which is 'private' is also a public realm when viewed from outside the compartment that one calls 'home.'

Notes:

1. Public Spaces of different kinds appeal to different sets of people. Saras Bagh for instance is an endearing and popular public park in Pune City. However, its location in relation to our residence makes it inaccessible on a daily basis.

2. Service Class is a term I am using to denote informal sector workers including domestic occupations like house maids, drivers, gardners, sweepers et al. These occupations are linked to formal residential developments, which in turn are linked to formal sector jobs. According to research, every formal sector job induces 7 informal sector occupations.

3. The idea of 'my' city is brought out by uniquely personal experiences. The city you belong to and experience is not the same for other sets of individuals, and the more aware we are of differences in perceived spaces, the more inclusive our city becomes. Of course, experiences can be designed, but creating the illusion of unique individual experiences, each meaningful in its own right, is not a design phenomenon, its a behavioural one, a camouflage technique adopted that projects outwards the internal perceptions of the viewer, making it an experience that the viewer cherishes. We do not all pick up the same souvenirs from a space we visit, because spaces affect us uniquely.

4. The end of German Bakery occurred much before the 2010 terror attacks, with the 'growth' of the O-hotel right opposite the narrow road, that lead to a severe social and economic distortions in the neighbourhood.

5. The establishment of the new bridge led to the Vimaan Nagar-Kalyani Nagar-Koregaon Park construction boom, and ended the activities on the road opposite HSBC. It is now a notoriously dark stretch of road where you can solicit (ironically) transgender prostitutes and possibly a variety of contraband.

In my own home-town of Pune, where I grew up, I can speak of a more concrete framework of these spaces. Pune through the years has had many memorable, but transient public spaces, such as the CCD spill-over space on East Street (MG Road)(1), because over the course of Real Estate gaining momentum in the city, these spaces have deteriorated, others have become more prominent, while several others have died. The East Street spill over for instance, is now a parking lot. Here, I need to make it clear that I am not going to discuss Pune Peth's (old city) since discussing (built) heritage while comparing it to a greenfield development such as Lavasa would be incorrect, as Lavasa, and other such developments would always lose out. Further, I would also like to make it clear that I am not defending a development like Lavasa, which come at severe environmental costs, but I do not believe in the grimly presented social implications of such developments either, because there is more active resilience in social laws than in natural (physical) laws. And if and when, the city of Lavasa achieves long-term crowding per square area (sustainable density), I believe the service classes(2) will find their way through informal spontaneous developments, the crack-in-wall solution. I am not saying that such routes of gaining urban space are correct, but simply that these systems exist and are inevitable, until a homogeneous society is achieved, which in itself would be an undesirable state, because it would lead to societal stagnation. If we were to consider evolution as a natural process of the city-organism life, then such disparities are required for constant upward movement- financial, aspirational, socio-cultural and even scientific innovation.

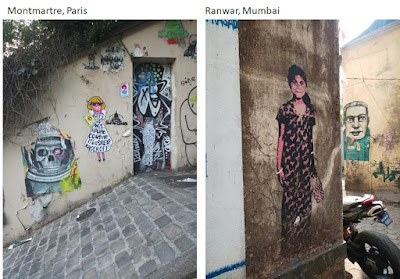

A case example for this kind of disparity leading to areas of significant cultural and artist innovation can be found in the urban villages and inner city areas of our cities. These areas fall in the amphibious quasi-legal no man's land between formal and unplanned, the regions most ripe for evolutionary phenomenon, the primordial soup of city-life, mixing together the molecules of many to eke out a few resilient beings, becoming the breeding grounds of many great Souvenir Spaces, each presenting a uniquely personal experience.(3) In the case of New Delhi for instance, places like Hauz Khas (village) became a 'spark' for youth-culture, expressionism and modern-Indic artistic vocabulary because these places are steeped in disparities- from socio-cultural and historical influences, to urban poverty, extremely distorted land markets, youth, influx of foreign nationals (probably initially drawn by historic value), and moneyed residential enclaves, to petty crime, drug peddling and prostitution. It is the intermingling of these social forces that led to the development of this 'fashionable bohemian' village, which now houses designer showrooms and cafes that are far removed from the birthing conditions of the 'open village' becoming more closed and limited both in appeal and affordability, and it is this lean towards homogeneity that will lead to the decline in social innovation.

In the case of Pune, sometime in 2002, HSBC's Corporate office sprouted in the far end of Kalyani Nagar, opposite the Wadia stud-farm, facing the River Mula-Mutha banks, and accessible to the large mixed income residential enclaves in the North-East quarter of the city. Interestingly, the Yerwada Urban Village and Slum, spatially the largest slum cluster in Pune, is also within a 5 km radius of this new development, as is the now infamous German Bakery, the Osho Ashram, Deccan College of Archaeology and Pune Airport. The River Mula-Mutha divides these areas laterally into two halves, and the road leading in from the airport further subdivides it into Slum and Middle/High Income Residential Enclave in the North, and Mixed used residential (water front, informal retail, commercial and residential colony) and the Osho Ashram influence zone in the South.

This was the era before the Kalyani Nagar mall explosion, and the time of the MTV Roadies launch. Two prominent participants of the show were residents of the colony, and with the half constructed road, the 'kids' soon found a playground for bike-racing and performing stunts like wheelies on an unwanted patch of road, in the 'middle' of nowhere so to speak. But that was the quality of the city which provided us with these very public avenues to just be. Between 1999 and 2005, we found the oddest places to 'break out'- the in the grassy hill top behind Lulla Nagar and NIBM, in the Salisbury Park graveyard, near Suicide Lake next to the airport, and at Khadakwasla lake. If we form a pattern, we begin to realize that these were all 'unplanned open spaces' in the heart of the city where we could just 'be'. And we were. These spaces were dark, not maintained, nature's slums, informal, random, and by and large, with a degree of safety that emboldened us to go there at night, and do what we want.

And in the case of Kalyani Nagar, it was there, in these betweens, in the narrow fringes of the river side wilderness, between the old bridge and the not yet complete new bridge, that thrived an active-innovation space, while on the other side of the river thrived our much beloved German Bakery (GB). Having not grown up in Delhi, I can only estimate the birthing conditions of Hauz Khas, but in my readings, the conditions seem almost alike. The restricted natural space (heritage monument in the case of Hauz Khas and private lands in the case of GB), the proximity to an urban village, a slum and an underground network of drugs and prostitution, foreign money, youth from nearby high-end residential enclaves, and a 'break-out'. But in the case of GB, it did not end very well, though it did not end very well for Pune as a whole. With the concreted access roads, inflated real estate prices, and the coming up of hotels, residential complexes, malls and commercial avenues, these flexible spaces vanished, becoming more regimented, more governed, and in turn less experimental and innovatory. (4) (5)

And in the case of Kalyani Nagar, it was there, in these betweens, in the narrow fringes of the river side wilderness, between the old bridge and the not yet complete new bridge, that thrived an active-innovation space, while on the other side of the river thrived our much beloved German Bakery (GB). Having not grown up in Delhi, I can only estimate the birthing conditions of Hauz Khas, but in my readings, the conditions seem almost alike. The restricted natural space (heritage monument in the case of Hauz Khas and private lands in the case of GB), the proximity to an urban village, a slum and an underground network of drugs and prostitution, foreign money, youth from nearby high-end residential enclaves, and a 'break-out'. But in the case of GB, it did not end very well, though it did not end very well for Pune as a whole. With the concreted access roads, inflated real estate prices, and the coming up of hotels, residential complexes, malls and commercial avenues, these flexible spaces vanished, becoming more regimented, more governed, and in turn less experimental and innovatory. (4) (5)

On the other end of the spectrum, in neo-cities like Lavasa, there has been an attempt by the designers to manufacture 'land uses' meant to become 'great public spaces'. I cannot argue on the technological merits of 'smartness', but if we go by the example of spontaneous social innovation cycles, leading to both Haute Couture, and demand for high-end real estate, it is not pragmatic to think that vitality, the spirit of revival, can be achieved through the vision of planning alone.

|

| Synthesized Public Space in Chandigarh (above) vs Manufactured Public Space at Lavasa(below) |

One of the aspects that we must understand is that 'great public spaces' are spaces were 'great' memories are formed. We may not like to admit it as urban planners and designers, but we cannot control how spatial quality psychological affects people, on the scale of a street to city. While architects may be successful in affecting people within the influence zone of a perceivable built environment, it is not possible for us to exercise that degree of control over ever increasing cities, both in sheer size (density/sqkm) and complexity. With Corbusier's Chandigarh model as a middling ground for planned cities we love to hate, but love nevertheless, we need to admit that people make great public spaces, whether a built environment is present or not. However, for people to be able to make spaces 'great' we as planners must allow 'diversity' and 'spatial complexity' to come face to face with each other. It is not an accident that when nature meets the exuberance of youth and when the very rich mingle with the very poor, the sparks of social innovation set fire to the machinery of critical thought, the very essence of humanity's purpose on the planet.

There is another aspect that we must understand when we speak about Souvenir Spaces, that is when we link the spatial quality of spaces with the ability to invoke us in psychological terms, we inherently link it to an experienced or felt temporal space. In simpler terms, a space will only mean something to us, if it reminds us of a pleasant lived experience, that is, it will make us nostalgic, or melancholic, and invoke in us a sense of 'longing' or perhaps even 'belonging'. However, it becomes essential to understand the Memory Retrieval Curve here, because different age-groups tend to use or experience similar spaces in different ways as they are forming (or remembering) memories. Over the course of our life, we go back to the memories we formed between the ages of 10 and 30, and it is perhaps for this age group that making public spaces 'great' or 'smart' is not particularly essential, but rather making them free (flexible from a regulatory perspective), informally governed, and completely 'safe'. This is one of the primary reasons for looking into what is refered to as 'Child friendly cities', but it is more than merely 'safety', as it is with creating memorable spaces with safety as an inbuilt device.

|

| Life Time Memory Retrieval Curve |

One of the things that I want to make clear here about Souvenir Spaces within the paradigm of architectural studies is the 'unboxing' of these spaces. Think of it like a series of cubes that are moving forward in time together, as well as moving laterally, that is, shifting places with each other simultaneously as well as chaotically (randomly). It is therefore is hard to illustrate such spaces and to plan them, and any depiction of such images would not sufficiently capture the dynamic nature of these places. However, it is possible through Films to tell these stories. This discussion would take us firmly into Walter Benjamin Territory, and that is a discussion for a different time.

Think of the Souvenir Spaces like like cubes or compartments of a metro train. The compartment is moving at a rapid speed in the forward direction. The pillars holding up the rail and the concourse, also move up and down simultaneously, from the roof of the compartment to the foundation of the metro-pillar. There are times when the train is moving that the points are non-aligned. The points also shift between the two sides of the metro pillars (left and right) and there for, for a Person experiencing the 'Present' it is impossible to determine which point is located where. It is also not possible to pinpoint with accuracy where the points will be in the future. It is only in hindsight, the 'known past', where there can be a point in spacetime when a suitable model, working model of the space can be determined, when all the points fall exactly where the design suggested.

This makes designing Souvenir Spaces in the public realm exceptionally difficult because now, the individual experiencing the present is no longer a single point perspective, but rather a collective. These discussions are particularly important, especially in the realm of housing studies. Housing, which is 'private' is also a public realm when viewed from outside the compartment that one calls 'home.'

Notes:

1. Public Spaces of different kinds appeal to different sets of people. Saras Bagh for instance is an endearing and popular public park in Pune City. However, its location in relation to our residence makes it inaccessible on a daily basis.

2. Service Class is a term I am using to denote informal sector workers including domestic occupations like house maids, drivers, gardners, sweepers et al. These occupations are linked to formal residential developments, which in turn are linked to formal sector jobs. According to research, every formal sector job induces 7 informal sector occupations.

3. The idea of 'my' city is brought out by uniquely personal experiences. The city you belong to and experience is not the same for other sets of individuals, and the more aware we are of differences in perceived spaces, the more inclusive our city becomes. Of course, experiences can be designed, but creating the illusion of unique individual experiences, each meaningful in its own right, is not a design phenomenon, its a behavioural one, a camouflage technique adopted that projects outwards the internal perceptions of the viewer, making it an experience that the viewer cherishes. We do not all pick up the same souvenirs from a space we visit, because spaces affect us uniquely.

4. The end of German Bakery occurred much before the 2010 terror attacks, with the 'growth' of the O-hotel right opposite the narrow road, that lead to a severe social and economic distortions in the neighbourhood.

5. The establishment of the new bridge led to the Vimaan Nagar-Kalyani Nagar-Koregaon Park construction boom, and ended the activities on the road opposite HSBC. It is now a notoriously dark stretch of road where you can solicit (ironically) transgender prostitutes and possibly a variety of contraband.

Comments

Post a Comment