Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam- Towards Swaraj of the Self

From the desk of Vitasta Raina

Time: Irrelevant

Innovative Ideas to Meet the Family Planning Challenges in India

The continuing population growth in India has brought thought exercises in sociologic and demographic studies to the forefront of the country’s development plans. At the same time much has already been debated about the current population, its salient features and the methods of population control such as increasing access to education. However, there is a glass-ceiling which surrounds the issue and certain critical topics within the demographical profile are often not broached.

At the same time, there is a need, since we are foremost a secular and socialist country, to respect the cultural and religious values of all segments of our population. And therefore, the dictatorial population control methods that seem to work in countries like China cannot be adopted here. It is thus, imperative to for us, the citizens of India to come out with a unique multi-pronged strategy for controlling our ever growing population, though it is noted that in recent times the growth rate has receded.

It is important for us now, at this stage of our urbanization, to recognize that it is not just that we have to meet the challenges of India, but that there are two separate Indian Identities within our country that present differing sets of challenges. The first are the issues of Urban India, which include instances of female foeticide, and extreme inequity among others, and the second set of issues are those of Rural India. In both cases though, the one thing that cannot be denied is that our family planning is overwhelmingly irresponsible.

With the changing nature and the widening gap between the rural and the urban, it is an important first step in our challenge to bring the populations closer, and increase their awareness of the issues that each of them face. This step is vital for understanding mass (population) motivation, which instead of being an urban vs. rural dynamic as it is currently perceived, is rather a complementary combination of the two.

This can be done by changing our understanding of what constitutes the sectors of rural and urban employment. Agricultural and allied primary sectors are largely seen as ‘rural’ though they are vital to the prosperity of the urban regions of the country. Food, the easy access, availability and affordability of which, gives people a sense of dignity and worth. Without this sense of dignity, it is not possible for people to find a balancing stability within themselves. The question of “quantity vs. quality” i.e. in crude terms, the sheer number of people versus a few, but highly motivated, healthy and productive people, can be addressed by the changing the value of their “self-worth” to the country.

In today’s globalizing times, since value is judged in GDP, it is important for us to break away from looking at cities as ‘engines of growth’ and to dissolve the sectoral lines between rural and urban, and allow certain sectors of manufacturing such as food-processing, which is at the present moment, an urban sector, to be seen as a component of rural employment. By paying our large, diverse and economically stressed rural populations, their right value for food production, we may indeed encourage them to look at themselves as more than just “working hands” and perhaps enhance their livability.

In psychological terms, when a human-being is debased and motivated to look at himself (or herself) as a lesser-person, and does not have control over his life nor possess the tools to express himself, he tends view reproduction as only preserving legacy (heirs). On the other hand, when he is equipped with the right tools, and has a sense of “Swabhiman” (dignity), his idea of who he is, and the impact he has on the world, changes for the better, and his inner motivation for preservation is replaced by the need for self-actuation and self-improvement. That is perhaps the greatest takeaway from the Gandhian principal of Swaraj, which is not just of a people over themselves, but of an individual person over himself.

At the same time, while we dissolve the barriers between urban and rural, we have to think in terms of governance. We have to think about the quality of education, of health care and of extending basic services to our population required to increase their self-dignity and self-worth. For this, we may need to look at establishing a dual form of governance.

At the present moment, we cannot ignore the quasi-feudal zamindari system in the country, nor the caste-based politics that fuels the intentional backwardness of certain sections of the population. For any developmental practise to be truly successful in providing basic educational and health reforms required for raising the living standards and self-values of individuals, which in turn has a positive impact on family planning, we need to go back and question our current panchayati raj system. At the same time, we need to also look at the representation of women in governance.

Today we find ourselves at the threshold of India’s ‘great urban awakening’ but it stands on the backbone of the fragile and fragmented rural populous. It is here that the Marxist ideology of social ownership of the means of production can be adopted. By eliminating sole ownership of land, we can alleviate the status of the landless labour, and by eliminating ‘representative democracy’, we can control the deleterious effects of caste based politics in the countryside. At the same time, we can promote the idea of women leaders in rural communities.

Thus, by equalizing the power structure in rural areas, and by bringing rural and urban population identities closer, the deep rooted issues of lack of education, and lack of sanitation and healthcare, which are at the heart of our population problem, can be resolved. It requires however, political will, and the acceptance that such change will require a concerted effort over the next five to ten years.

There is another issue that is linked to meeting the family planning challenge of India- Adoption. This is again, as with several social issues such as female foeticide in urban India, intrinsically linked to economics. It is not an unknown fact that the ‘modern nuclear family’ is a direct consequence of western classical economics, a brain child of capitalism and an indicator of a consumerist society. We need to erase the taboo and stigma surrounding the idea of adoption, and remove the ‘nature vs. nurture’ debate from the mainstream media.

If we go back to the traditional village system, the remnants of which are visible in the notorious Khap Panchayats in North India, we begin to understand that a child does not belong only to his parents, but rather to an entire community. It is this idea that ‘the child is more than the sum of his (or her) parents’ that needs to become a normal phenomenon. It is only when the larger society does not think twice about the whether the child is a biology progeny or a child of adoption, is when we can leverage the power of adoption, and look upon it as a viable solution to India’s population challenge.

That adoption is synonymous with “Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam” (the world is one family) needs to be driven home, and with the help of mass media, it may become a possibility. But for this, we first need to dissolve the many barriers between our diverse ideas of India.

Time: Irrelevant

Innovative Ideas to Meet the Family Planning Challenges in India

The continuing population growth in India has brought thought exercises in sociologic and demographic studies to the forefront of the country’s development plans. At the same time much has already been debated about the current population, its salient features and the methods of population control such as increasing access to education. However, there is a glass-ceiling which surrounds the issue and certain critical topics within the demographical profile are often not broached.

At the same time, there is a need, since we are foremost a secular and socialist country, to respect the cultural and religious values of all segments of our population. And therefore, the dictatorial population control methods that seem to work in countries like China cannot be adopted here. It is thus, imperative to for us, the citizens of India to come out with a unique multi-pronged strategy for controlling our ever growing population, though it is noted that in recent times the growth rate has receded.

It is important for us now, at this stage of our urbanization, to recognize that it is not just that we have to meet the challenges of India, but that there are two separate Indian Identities within our country that present differing sets of challenges. The first are the issues of Urban India, which include instances of female foeticide, and extreme inequity among others, and the second set of issues are those of Rural India. In both cases though, the one thing that cannot be denied is that our family planning is overwhelmingly irresponsible.

With the changing nature and the widening gap between the rural and the urban, it is an important first step in our challenge to bring the populations closer, and increase their awareness of the issues that each of them face. This step is vital for understanding mass (population) motivation, which instead of being an urban vs. rural dynamic as it is currently perceived, is rather a complementary combination of the two.

This can be done by changing our understanding of what constitutes the sectors of rural and urban employment. Agricultural and allied primary sectors are largely seen as ‘rural’ though they are vital to the prosperity of the urban regions of the country. Food, the easy access, availability and affordability of which, gives people a sense of dignity and worth. Without this sense of dignity, it is not possible for people to find a balancing stability within themselves. The question of “quantity vs. quality” i.e. in crude terms, the sheer number of people versus a few, but highly motivated, healthy and productive people, can be addressed by the changing the value of their “self-worth” to the country.

In today’s globalizing times, since value is judged in GDP, it is important for us to break away from looking at cities as ‘engines of growth’ and to dissolve the sectoral lines between rural and urban, and allow certain sectors of manufacturing such as food-processing, which is at the present moment, an urban sector, to be seen as a component of rural employment. By paying our large, diverse and economically stressed rural populations, their right value for food production, we may indeed encourage them to look at themselves as more than just “working hands” and perhaps enhance their livability.

In psychological terms, when a human-being is debased and motivated to look at himself (or herself) as a lesser-person, and does not have control over his life nor possess the tools to express himself, he tends view reproduction as only preserving legacy (heirs). On the other hand, when he is equipped with the right tools, and has a sense of “Swabhiman” (dignity), his idea of who he is, and the impact he has on the world, changes for the better, and his inner motivation for preservation is replaced by the need for self-actuation and self-improvement. That is perhaps the greatest takeaway from the Gandhian principal of Swaraj, which is not just of a people over themselves, but of an individual person over himself.

At the same time, while we dissolve the barriers between urban and rural, we have to think in terms of governance. We have to think about the quality of education, of health care and of extending basic services to our population required to increase their self-dignity and self-worth. For this, we may need to look at establishing a dual form of governance.

At the present moment, we cannot ignore the quasi-feudal zamindari system in the country, nor the caste-based politics that fuels the intentional backwardness of certain sections of the population. For any developmental practise to be truly successful in providing basic educational and health reforms required for raising the living standards and self-values of individuals, which in turn has a positive impact on family planning, we need to go back and question our current panchayati raj system. At the same time, we need to also look at the representation of women in governance.

Today we find ourselves at the threshold of India’s ‘great urban awakening’ but it stands on the backbone of the fragile and fragmented rural populous. It is here that the Marxist ideology of social ownership of the means of production can be adopted. By eliminating sole ownership of land, we can alleviate the status of the landless labour, and by eliminating ‘representative democracy’, we can control the deleterious effects of caste based politics in the countryside. At the same time, we can promote the idea of women leaders in rural communities.

There is another issue that is linked to meeting the family planning challenge of India- Adoption. This is again, as with several social issues such as female foeticide in urban India, intrinsically linked to economics. It is not an unknown fact that the ‘modern nuclear family’ is a direct consequence of western classical economics, a brain child of capitalism and an indicator of a consumerist society. We need to erase the taboo and stigma surrounding the idea of adoption, and remove the ‘nature vs. nurture’ debate from the mainstream media.

If we go back to the traditional village system, the remnants of which are visible in the notorious Khap Panchayats in North India, we begin to understand that a child does not belong only to his parents, but rather to an entire community. It is this idea that ‘the child is more than the sum of his (or her) parents’ that needs to become a normal phenomenon. It is only when the larger society does not think twice about the whether the child is a biology progeny or a child of adoption, is when we can leverage the power of adoption, and look upon it as a viable solution to India’s population challenge.

That adoption is synonymous with “Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam” (the world is one family) needs to be driven home, and with the help of mass media, it may become a possibility. But for this, we first need to dissolve the many barriers between our diverse ideas of India.

| ||

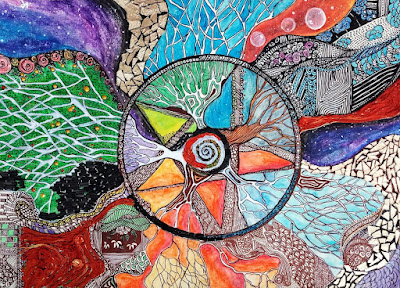

| Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam: The World is One Family | Image (c), Vitasta, 2017 |

Comments

Post a Comment